How Strategy and Psychology Work Together to Perfect Pricing (well, almost)

Note: Republishing this post I shared on the Medium paid subscription a few years ago. This was originally written in March 2015.

Pricing: Sensitive, Scary, and Crucial

Pricing is one of the most powerful yet under-appreciated levers in business. Good pricing has the power to increase Customer Lifetime Value, make unprofitable businesses thrive, and completely change Brand perception.

Done poorly, it can doom quality products to failure, tarnish reputations, and really piss off customers. Customers are sensitive to even tiny changes in price, and the consequences impact a company’s survival. What a fun topic!

In this Edition we’ll take a look at Pricing in the following ways:

Strategic Prices — How Pricing Tactics fit into your Strategy

Psychology of Pricing — Tactics and Tricks that Companies use

Case Studies of Successful Pricing — What works and who’s winning

Remember that the effectiveness of these ideas is radically different by Industry and Product. We’ll cover lots of different examples — it’s up to you to decide which are applicable to you.

How Pricing Complements Strategy

The curious thing about pricing is that it’s impossible to do perfectly. In most cases, the best we can hope for is ‘not completely terrible.’ The reason for this is the tension between the obvious goal of Pricing (Profit Maximization) and the non-obvious goals (not piss off your customers or diminish incentive to purchase, and grow the business).

How WhatsApp Won it’s Market — Smart Pricing

To know which factors to optimize for, deeply understand your business goals. For a messaging app, the most important thing is to grow and own the market. Charging new customers was a barrier that would impede growth. WhatsApp knew exactly what it was doing when it committed to charge $0.99 per year for their service, with the first year free.

WhatsApp’s “free for the first year” model allowed them to solve for both business requirements — it got users over the dreaded Penny Gap and onto the platform, contributing to its rapid growth and creating lock-in.

The eventual revenue meant that WhatsApp didn’t have to worry about monetization through advertising — something the founders are still against. In addition to solving this challenge, the year trial gives users enough time to try and get hooked on the product, but still sets the precedent from the beginning that WhatsApp will not be free forever.

This last point is an important one — customers know that the charge is coming for a whole year in advance. A genius way to play the long game.

How Platform Companies think about Pricing

This post from Bill Gurley — suggested by Ray Stern and Chris Zook — goes into detail on how pricing works for platforms and marketplaces. The strategy for these companies requires prioritizing long-term Market Share over short-term Profit Maximization. Here’s why:

If your objective is to build a winner-take-all marketplace over a very long term, you want to build a platform that has the least amount of friction (both product and pricing). High rakes are a form of friction precisely because your rake becomes part of the landed price for the consumer. If you charge an excessive rake, the pricing of items in your marketplace are now unnaturally high (relative to anything outside your marketplace).

In order for your platform to be the “definitive” place to transact, you want industry leading pricing — which is impossible if your rake is the de facto cause of excessive pricing. High rakes also create a natural impetus for suppliers to look elsewhere, which endangers sustainability.

Most of this post is specially directed toward Platform companies, but the last paragraph is a powerful, broad point about pricing in general:

There’s always a downside to maximizing prices.

Number one on the list of Peter Drucker’s Five Deadly Business Sins is “Worship of high profit margins and premium pricing.” As Drucker notes: “The worship of premium pricing always creates a market for the competitor. And high profit margins do not equal maximum profits. Total profit is profit margin multiplied by turnover. Maximum profit is thus obtained by the profit margin that yields the largest total profit flow…”

Most venture capitalists encourage entrepreneurs to price-maximize, to extract as much rent as they possibly can from their ecosystem on each transaction. This is likely short-sighted. There is a big difference between what you can extract versus what you should extract. Water runs downhill.

Change The Damn Prices

This Short post from Intercom.io shows four different approaches to increase price, and ways to raise them without causing turmoil.

The whole post is great, and my favorite is this image and short paragraph about the power of changes in price — it can transform your business.

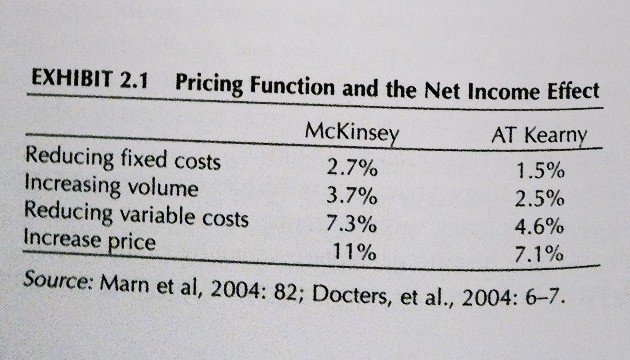

Nothing impacts your bottom line better than improving your pricing. Two independent studies by McKinsey & A.T. Kearney , both concluded that a 1% increase in pricing affects a company’s profits more than any other change. In short, of all the things you can spend time tweaking, pricing will yield the best return. For some reason deploying your product and never changing it seems ludicrous, yet deploying your pricing and never changing it doesn’t.

This post was also suggested by Ray Stern and Michael Gelphman.

How to Set an Initial Price

This Pricing Guide from Sequoia, contributed by Preet Anand, is a great resource that has a few different ways to look at pricing, and examples from Linkedin and Evernote. It also has a great section on Perceived Value:

Usually, companies fixate on the gap between how much their products cost to make and how much they charge for them. But you should also focus on the gap between your price and how much value customers think it delivers, a concept known as perceived value.

Companies often assume that if sales are slow they need to cut prices. But more often, Dearing says, “If nobody’s buying my product, it’s because the gap between price and perceived value either doesn’t exist or it’s not large enough.”

Sequoia’s Guide ends with a Pricing Worksheet and walkthrough, which is a great exercise to do even for a hypothetical product you have in mind, just to get good at the thought process.

Get Weird With Pricing

No one is telling you that you can’t do something with pricing. If you want to try to collect money 2 years in advance of product delivery, people on Kickstarter are doing that all the time. Some companies set group rates for those who bring their friends to receive discounts. Experiments are happening every day in Pricing, and there’s always something new to try.

These few ideas from Scott McCloud on possibilities of monetizing webcomics could give you some ideas on what might work for you:

Scott McCloud’s amazing full Webcomic here: http://www.scottmccloud.com/1-webcomics/icst/icst-6/icst-6.html

Another notorious example of hilarious pricing is Chocolat, which offers a free trial of it’s software, and when the trial expires…

How Psychology Affects Pricing

Pricing isn’t a Math Problem — it’s a Psychology Problem. Understanding what customers are happy to pay for various sets of products and services. Let’s see some of the Psychological forces in Pricing, and how to wield them:

Pavlovian Association: Higher Price = Better Product

There’s an amazing phenomenon in pricing, where an increase in price leads to an increase in sales because of a basic guideline that is programmed into all of us. We’re so used to better products costing more, that when something costs more we assume that it is better. Charlie Munger (One of the wisest men alive, right-hand man to Warren Buffett) talks about this in The Psychology of Human Misdjudgement:

Here’s a short Forbes article citing Psychologist Robert Cialdini on how customers increasingly use the “high price = high quality” heuristic in “markets in which people are not completely sure of how to assess quality.”

Here’s a real-life example from Cialdini’s incredible book, Influence:

I got a phone call one day from a friend who had recently opened an Indian jewelry store in Arizona. She was giddy with a curious piece of news. Something fascinating had just happened and she thought that, as a psychologist, I might be able to explain it to her. The story involved a certain allotment of turquoise jewelry she had been having trouble selling. It was the peak of the tourist season, the store was unusually full of customers, the turquoise pieces were of good quality for the prices she was asking; yet they had not sold. My friend had attempted a couple of standard sales tricks to get them moving. She tried calling attention to them by shifting their location to a more central display area; no luck. She even told her sales staff to “push” the items hard, again without success.

Finally, the night before leaving on an out-of-town buying trip, she scribbled an exasperated note to her head saleswoman, “everything in this display case x 1/2,” hoping just to be rid of the offending pieces, even if at a loss. When she returned a few days later, she was not surprised to find that every article had been sold. She was shocked, though, to discover that because the employee had read the “1/2″ in her scrawled message as a “2,” the entire allotment had sold out at twice the original price!

Tourists who purchased this double-priced jewelry were following a simple rule they’ve known their whole life: “You get what you pay for.”

So, double the price and see if that helps sales! It’ll certainly help margins. If this one is too small or vague of an example for you, check out this passage from Playing to Win about how Proctor & Gamble determined the price for a product you’ve definitely seen:

Listro recalls the testing that went on to determine the pricing strategy for Olay Total Effects: “We started to test the new Olay product at premium price points of $12.99 to $18.99 and got very different results at those price points.” At $12.99 there was a positive response and a reasonably good rate of purchase intent. But most of the subjects who signaled a desire to buy at $12.99 were mass shoppers. Very few department store shoppers were interested at that price point.

“Basically,” explains Listro, “we were trading people up from within the channel.” That was good, but not enough. At $15.99, purchase intent dropped considerably. Then, at $18.99, purchase intent went back up again — way up. “So $12.99 was good, $15.99 not so good, $18.99 great.”

“$15.99 was no-man’s land — way too expensive for a mass shopper and really not credible enough for a prestige shopper.”

Price is a choice that determines which customers you’re speaking to, and which you’ll attract. This is a powerful, counterintuitive effect that you won’t get from the Economic or a math-based approach to pricing.

Pricing for Relativity (Or Contextual Pricing)

Paying attention to the context a Price is presented in is crucial, because we humans only evaluate decisions on a relative (rather than absolute) scale. Rory Sutherland, Vice Chairman of Ogilvy, explains it this way in a recent interview, suggested by Preet Anand:

It’s not completely relative, but people by and large don’t have an internal measure of pleasure. Classical economics tends to assert that people have this internal measure of utility of value, and that it’s an absolute consistent measure between categories, so we can decide whether it’s more valuable to have a glass of wine in a pub, which costs 5 pounds, or to have a hundred cups of tea at home, which probably costs about 5 pounds.

My contention (and I’m also supported by most economists and behavioral economists in this) is there is no such internal unit, that we don’t judge value according to some absolute overall measure of our own well-being, that actually what we tend to do is we choose something comparable, look at whether what we’re being offered is more expensive than usual or less, whether it’s better or worse, and we decide accordingly.

To give you an example of this, people happily pay 2.50 pounds certainly 2.00 pounds for a cup of tea at Starbucks to take away in a paper cup. They pay roughly 1 or 2 pence for a tea bag. Now, you can’t realistically say that the cup of tea you purchased from Starbucks is 100 times more enjoyable than the cup of tea you actually that you draw at home, may turn out to be a worse cup of tea.

This psychological trait is the reason that ideas like Decoys are effective in Pricing. The Decoy Effect in Price Tables shows how to contextualize the preferred purchase option to make it seem like the best option for customers. (Thanks to Michael Gelphman for that suggestion)

And here is another post from Stanford Business School about the power of comparison pricing, and how it can backfire. Be thoughtful about the comparisons made between products.

Visuals of Pricing and other Psychology Tricks

Aside from Association and Relativity, there are also many small optimizations that can be made around how prices are displayed that can influence decisions.

Everything about how a price is chosen and displayed can affect purchases, from the typeface, font size, inclusion of a dollar sign, decimals, anchoring, and more… let’s take a look:

ConversionXL has an incredible post that rounds up a LOT of these little tricks and has them all in one post with links to studies and experiments that back them up. Start there and you’ll get a flood of great ideas. Thanks to Michael Gelphman and Ray Stern (yes, again) for suggesting that post.

This short post from NeuroScienceMarketing is about the pros and cons of offering prices that are rounded ($100) or precise ($97.32). Take-aways are summed up by the graphic below. Great suggestion from Dan Thomas.

3 Ways To Optimize Product Pricing with Psychology, suggested by Michael Gelphman, has great sections on two common tactics: The power of adding ‘Free’ offerings, and the combination of Left-Digit Anchoring and prices that end in ‘9'.

Gumroad’s post on their own pricing data shows that prices that end in decimals have much higher conversion rates than whole numbers. Suggested by Derek Baynton.

What are you Actually Selling?

Price isn’t just about the Product — price is about the perceived value of what you’re selling. $4 for cup of coffee is a massive markup, but the experience of getting Starbucks is worth that to some people.

Does that mean that the effectiveness of Marketing means that a Business can charge a higher price for the same product? YES! What a miracle that is.

Here’s a post on a study from Stanford Business School that shows that Marketing messages that focused on Time rather than Value attracted more customers — even at a higher price point. That’s amazing.

Case Studies and Further Reading

Here’s a list for the die-hard to want to go deeper on Pricing resources:

Virgin Mobile Case Study from Harvard Business School.

Rethink your Pricing Strategy from Sloan Business School at MIT (suggested by Ray Stern).

Tear-Down of HubSpot’s Saas Pricing Model by the Price Intelligently Blog. Great for any recurring-revenue business.

If you’re in the Saas world, Ninan Thampy published a collection of his own favorite posts on Saas Pricing that may be helpful.

Product Pricing Primer for Software Products by Eric Sink, suggested by Chris Zook.

If you want to pick up some regular places to read continuously on Pricing, here are a few suggestions:

Price Intelligently, suggested by Kenny Fraser.

Iterative Path, suggested by Dan Thomas.