The Ancient Origins of Storytelling and How You Can Apply Them In Your Life

Note: Republishing this post I shared on the Medium paid subscription a few years ago. This was originally written in February 2016.

Why Story Matters

The most profound way to look at storytelling is to say that it is the defining characteristic of being human. Which is not an overstatement, but more of a biological fact.

Story is what makes Homo Sapiens unique

In Sapiens, Yuval Harari talks about the Cognitive Revolution as the change that enabled us to begin to cooperate, learn, and take over the world:

The truly unique feature of our language is not its ability to transmit information about men and lions. Rather, it is the ability to transmit information about things that do not exist at all. As far as we know, only Sapiens can talk about entire kinds of entities that they have never seen, touched, or smelled.

This ability to speak about fiction is the most unique feature of Sapiens language. […] Fiction has enabled us not merely to imagine things, but to do so collectively. We can weave common myths such as the biblical creation story or the nationalist myths of modern states. Such myths give Sapiens the unprecedented ability to cooperate flexibly in large numbers.

Story, at the most basic level, is a fiction designed to unify people. By experiencing something through story, people’s understandings begin to overlap and we can better coordinate and work with one another.

While Sapiens is not explicitly about story, the explanations of how social constructs like religion and money that unify humanity have their roots in story are fascinating and give great context to learning about Storytelling.

Thanks to Aaron Wolfson for suggesting Sapiens as a resource here.

How Story Affects Us

The Storytelling Animal, contributed by Nathan Bashaw, is a fantastic book that explores how thoroughly this ability to create fiction has permeated our lives, and what it does to us.

Story actually creates more than emotional empathy with a character, there is a physical response from our bodies:

Mirror neurons in our brains re-create for us the distress we see on the screen. We have empathy for the fictional characters — we know how they’re feeling — because we literally experience the same feelings ourselves. When we watch movie stars kiss onscreen, some of the cells firing in our brains are the same ones that fire when we kiss our lovers. “Vicarious” is not a strong enough word to describe the effect of these mirror neurons.

[…] Stories affect us physically, not just mentally. When the protagonist is in a tight corner, our hearts race, we breathe faster, and we sweat more.

This is a level of commitment to story that leaves lasting memories and impressions, and why story is such a powerful tool for teaching and inspiration — good stories aren’t just heard, they are felt.

The Storytelling Animal goes on to explore how Storytelling defines us by exploring how children instinctively create stories, how culture and morals are passed on through story, and moments in human history that have been changed by a simple story.

Story matters because we are defined by our storytelling ability. The way that we can create and share ideas with each other was born, perfected, and perpetuated in story. Storytelling (and story listening) is an evolutionary trait refined over thousands of years to unify and coalesce us as a species.

How Story Works

Storytelling can be elegantly simple or bafflingly complex, and everyone seems to have their own secret to ‘deconstructing’ story and explaining what pieces are important and what works. Of course, there are some very core principles that are foundational, which is where we will start.

The Most Basic Story Structure

Stories have three parts: beginning, middle, and end. No matter what else happens, it has those three things. But there are very important things that must happen in each of those parts, that forms the arc of the story and makes it a powerful experience for the listener.

This TED Talk from British literary agent Julian Friedmann does a beautiful job of explaining it (at about 7:00):

The three-act structure is a function of how the human brain works. Aristotle described the formula 2,5000 years ago. It worked then, and it works today. The Story Structure is three words: Pity, Fear, Catharsis.

You need to make the audience feel pity for a character. You do that by making them go through an undeserved misfortune. What that does is enables the audience to emotionally connect with the character. Once the wroter has established that emotional connection, the writer has some control over the audience.

You then put the character into worse and worse situations, and because of the emotional connection, the audience feels fear.

When you release the character from the danger, the audience feels the catharsis as its own.

Catharsis is actually the result of not any intellectual activity, but of chemicals being released in the bloodstream.

These three parts have been called many different things in many different places (hooks, inciting incidents, crisis, climax, etc) but those are semantics. I like Friedmann’s description because it is powerful and memorable. It describes the audience’s emotions, not the writer’s technique. If your story can create pity, fear, and catharsis, your audience will feel it.

Friedmann finishes his talk with a beautiful thought which is a crucial aspect of story: to remember that it is always about the audience.

Please don’t forget that you have to entertain us. You have to enable us to look at ourselves. Because when we’re looking at the screen, we’re not looking at the actors, we’re not looking at the characters, and we’re certainly not looking at you. We are looking at ourselves.

Story requires the effort of the audience. It requires us to lean in, to project ourselves into the place of that character, to create our emotional responses, and to take that character’s experience into our own lives.

All Stories are the Same

In the vast universe of stories that have been created by humans, from myths to comic book movies, there are really only a handful of ‘types of story.’

Storytelling has a shape. It dominates the way all stories are told and can be traced back not just to the Renaissance, but to the very beginnings of the recorded word. It’s a structure that we absorb avidly whether in art-house or airport form and it’s a shape that may be — though we must be careful — a universal archetype.

This short post in The Atlantic called All Stories Are The Same does a good job of showing the similarities of the ‘shape’ of so many stories without oversimplifying into a rigid structure.

Knowing that stories all branch out from the same trunk is reassuring to those of us trying to learn about them, because it is an infinitely complex language made up of only a few defined building blocks. And if we can understand those blocks, then we can make sense of this massively complex universe of story that surrounds us.

Thanks to Jack Mara of 10thoughts for the suggestion!

Story is Driven by Mystery

JJ Abrams (TV/Movie writer and director) famous for Star Trek, Lost, the new Star Wars, and more is a master of storytelling. And his secret is mastering mystery.

He draws people in by giving them questions, curiosities to chase, theories to prove. Here is an excerpt from his (hilarious) TED talk about Mystery:

What are story but Mystery boxes? In TV, the first act is actually called the teaser — it is the big question, so you’re drawn into it, and of course there’s another question, and on and on.

This is a very simple and powerful storytelling technique, to withhold key information to create curiosity and engagement. Beyond the suspense created by the uncertainty of the ultimate outcome, there can be small mysteries throughout the story that pull your audience in.

Thanks to Brian Sloss of Opower for contributing this talk!

How to Story

Given the immense power of story, of course we now wonder how to put this art to work ourselves. Whether we want to entertain friends, nail a job interview, inspire co-workers or just tell a good bedtime story, storytelling has some way to benefit our lives.

Secret Structure of Great Stories

I love to include an ‘if you only know one thing’ in these posts whenever possible. While lots of these resources are important and helpful to learning about the context of story and specific applications, this TED talk from Nancy Duarte is a great blend of high-level and applicable knowledge:

She deconstructs and compares Martin Luther King Jr’s “I have A Dream” speech and Steve Jobs iphone launch, and shows us how simple and effective storylines can be.

As the most basic, story alternates exploring ‘what is’ and ‘what could be’. This inspires the audience to drive toward the new bliss, and assimilate what was possibility into their worldview as a new belief.

6 Basic Rules of Story

The master of The Moth (which is a great event/podcast based on story), Margo Leitman as a great short post where she summarizes her advice on storytelling: 6 Rules for Great Storytelling.

It guides you away from the most common storytelling mistakes, and gives you a quick checklist for having a solid story. A short read, worth keeping on hand.

Thanks David Baker for suggesting this post and the book, Long Story Short.

Pixar’s Storytelling Lessons

If there is one organization in America that understands storytelling, it is Pixar. Their string of cultural hits is in large part due to their devotion to the art of story, and the discipline to rework a movie for polished perfection.

Audiences admire a character more for trying than for their successes.

This set of slides has Pixar’s 22 Rules of Phenomenal Storytelling, which are a good set of guiding principles. Some of them are specific to those writing movies or novels, but some are gems of overall story knowledge:

Pull apart stories you like. What you like in them is a part of you; you’ve got to recognize it before you can use it.

It is interesting to read these and see how much you can feel these principles in Pixar’s movies. We appreciate good stories, but we don’t often know what makes them good or why they feel so good to us until we read things like this that reveal the mechanics of story.

Thanks to Jason Evanish and Ben Kinnard for suggesting this resource!

The Deep Dive: Story Grid

This is probably overkill for anyone who is not writing a book or movie, but The Story Grid (contributed by Kevin Espiritu) is the best book for understanding complex story structure and the interplay between internal and external struggles.

Written by Editor Shawn Coyne, it details the tool that he uses to evaluate and improve books in an attempt to turn them into bestsellers and timeless works of art.

The Story Grid shows, in detail, how tensions are created and released throughout stories, and why some stories work and others fall flat. While clearly written for those in the literary world, it does have applicable lessons for anyone working on a large-scale creative project.

Applying Storytelling to Business

Storytelling is such a pervasive topic that it has the opportunity to affect nearly every aspect of business: hiring, sales, recruiting, partnerships, etc. Really, it is a method of communication with enormous leverage if we can apply it in the right ways.

This section is the practitioner’s guide — how to apply story to your business to see tangible results.

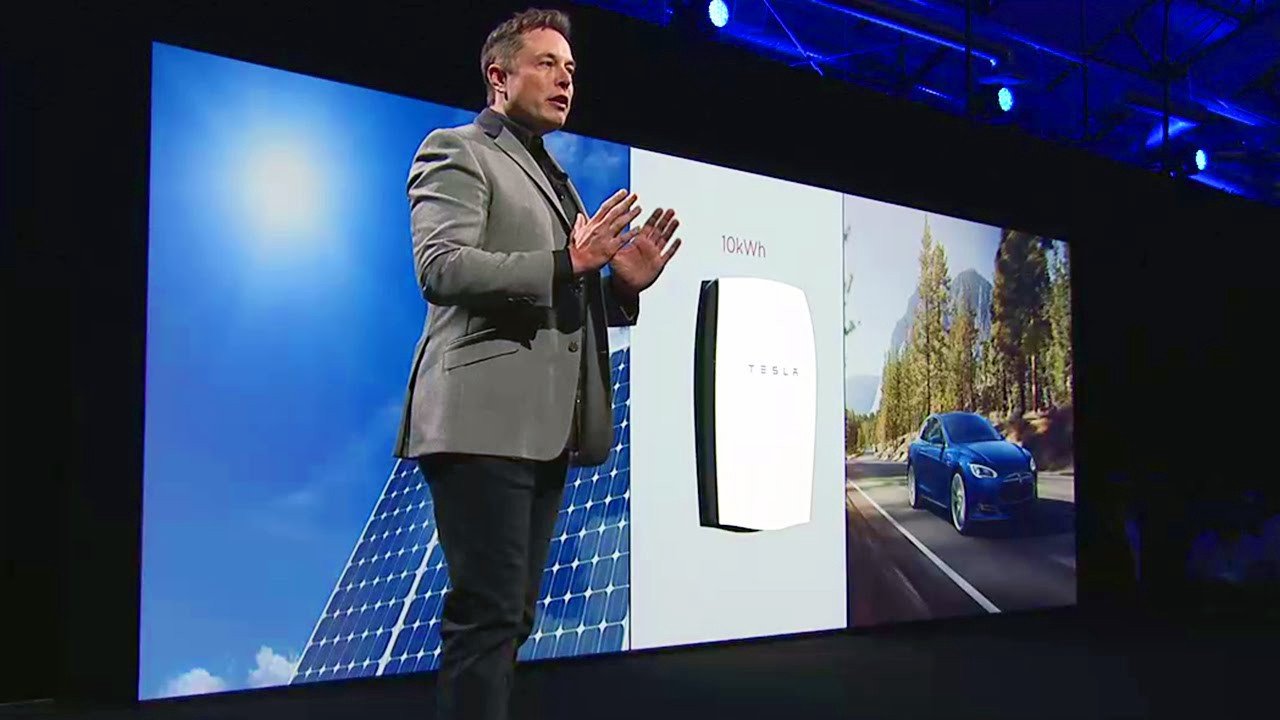

Deconstructing Elon Musk’s Presentations

This short read by Andy Raskin is incredibly popular because it breaks down the elements of a good pitch into the basic blocks of story. It is a very simple post, and gives a clear guide to format your product pitch in similar fashion.

Here is the structure:

Name the Enemy

Answer “Why now?”

Show the Promised Land

Identify Obstacles + Strategies

Present Evidence of Solution

You notice a similar structure to the multiple story structures we saw above. This is a very tactical translation of the story principles into business-speak, and gives you what is basically a mad-libs for creating a killer pitch.

As for step one, Name an Enemy, Raskin has a separate post about that called Who is your Darth Vader. If it isn’t immediately obvious what your enemy is, check that resource out.

(I personally find this to be an excellent exercise. Some of the enemies of Evergreen are: Shitty Content Marketing, SEO garbage, Churned-out Listicles, page-view optimizing republishers, shiny object syndrome, and ignorance)

Thanks to Abhishek Bhalla and Preet Anand for suggesting Andy Raskin.

All Marketers Tell Stories

Of course, Seth Godin had to make this list. His tiny little book, All Marketers Tell Stories fits perfectly with our set of resources. It builds upon the background we have with how integral stories are to our lives, and explores how to create stories in the marketing context.

My favorite point of Godin’s is that stories aren’t meant to change people — but to find the beliefs that already exist in your audience:

The best stories don’t teach people anything new. Instead, the best stories agree with what the audience already believes and makes the members of the audience feel smart and secure when reminded how right they were in the first place.

[…] Runaway hits like LiveStrong fund-raising bracelets take off because they match the worldview of a tiny audience — and then that tiny audience spreads the story.

This little book doesn’t take more than an hour to read, and it is densely packed with helpful thoughts about how to craft a story to represent a business and find your audience.

Thanks Aaron Wolfson for an incredibly thorough Godin recommendation.

The Leader’s Guide to Storytelling

The Leader’s Guide to Storytelling (suggested by Nick Seguin) reads like the field guide to using Storytelling in the business world. It starts high-level, and dives deep into the details of storytelling in the workplace in a variety of contexts.

This book has notes on writing and delivering these stories, in situations from establishing yourself in the company to brand-building and managing internal communications.

In Summary: There is a long way to go

We’ve covered a lot of ground here, from the intertwined roots of storytelling in humanity to the applications of that knowledge in an office context.

While there are some great resources here, I get the sense that there is a lot left to learn and apply from the lessons of Storytelling. This doesn’t feel like a well-explored concept yet, and I can see a path toward far more thorough understanding and application in many different directions.

But maybe that is part of the magic of story — that it can’t be dissected, analyzed, and reassembled because of the difficulty in studying how perception occurs and effects are subtle.

All I know is that I am grateful to have this ‘story’ lens on the way I look at the world now. It is fascinating to hear stories as something that someone has crafted for us, and to think about what the implications of it will be for every individual who hears it.