How to Fire Someone: How to Decide, When to do it, and How to be Guilt-free

Note: Republishing this post I shared on the Medium paid subscription a few years ago. This was originally written in May 2015.

One of the worst work experiences anyone can have is being fired or having to fire someone. It’s not a comfortable topic, nor one people look forward to discussing. That means it is full of opportunities…

We’ll take a look at how some of the world’s best managers and companies think about firing, and what we can learn that can remove the gut-wrenching tension, and empower us to build ever-better businesses.

When to Fire…

Why Warren Buffett Fires People

Warren famously invests in management, specifically to avoid firing people. He does not enter companies where a management change is part of the plan.

“One thing I don’t like is when I have to make a change in management, when I have to tell somebody I think somebody else can do a better job.”

That’s an interesting way to phrase it — that someone else could do a better job. Not that the manager is bad or incompetent or doing anything wrong — simply that there is room for improvement and he has a duty to make that improvement. That doesn’t make it easy for him though:

“It’s pure agony, and I usually postpone it and suck my thumb and do all kinds of other things before I finally carry it out.”

It seems like most people are the same way — firing may be the most-procrastinated task in the business world. No one wants to pull the trigger.

When the firing decision is not based on performance, but on infractions of ethical or moral grounds, things are much more clear cut. Here’s Buffett:

“Lose money for my firm and I will be understanding. Lose a shred of reputation for the firm and I will be ruthless.”

As an employee working under him I understand that completely. It’s a rule that I’d be proud to work under. This iron rule is a great setup for a story from Buffett’s friend and business partner…

Charlie Munger’s Favorite Firing Story

Charlie Munger, for those uninitiated, is Warren Buffett’s right-hand man at Berkshire. He’s a brilliant investor, billionaire, lawyer, and thinker. This story is excerpted from one of his more famous talks, The Psychology of Human Misjudgement:

What’s quoted here is the only part on firing, but the whole thing is great.

This is the story of John Gutfreund, who was CEO of Salomon Brothers until Warren Buffett forced him to resign in 1991. He decided not to fire someone who behaved immorally, which destroyed his reputation and his career. You may confront a similar challenge someday:

Here I think we should discuss John Gutfreund. This is a very interesting human example, which will be taught in every decent professional school for at least a full generation. Gutfreund has a trusted employee and it comes to light not through confession but by accident that the trusted employee has lied like hell to the government and manipulated the accounting system, and it was really equivalent to forgery. And the man immediately says, “I’ve never done it before, I’ll never do it again. It was an isolated example.” And of course it was obvious that he was trying to help the government as well as himself. […]

At any rate, this guy has been part of a little clique that has made, well, way over a billion dollars for Salomon in the very recent past, and it’s a little handful of people. And so there are a lot of psychological forces at work, and then you know the guy’s wife, and he’s right in front of you, and there’s human sympathy, and he’s sort of asking for your help, which encourages reciprocation, and there’s all these psychological tendencies that are working, plus the fact he’s part of a group that had made a lot of money for you. At any rate, Gutfreund does not cashier (fire) the man, and of course he had done it before and he did do it again.

Well, now you look as though you almost wanted him to do it again. Or God knows what you look like, but it isn’t good. And that simple decision destroyed Jim Gutfreund, and it’s so easy to do.

Now let’s think it through like the bridge player, like Zeckhauser. You find an isolated example of a little old lady in the See’s Candy Company, one of our subsidiaries, getting into the till. And what does she say? “I never did it before, I’ll never do it again. This is going to ruin my life. Please help me.” And you know her children and her friends, and she’d been around 30 years and standing behind the candy counter with swollen ankles. When you’re an old lady it isn’t that glorious a life. And you’re rich and powerful and there she is: “I never did it before, I’ll never do it again.” Well how likely is it that she never did it before?

If you’re going to catch 10 embezzlements a year, what are the chances that any one of them — applying what Tversky and Kahneman called baseline information — will be somebody who only did it this once? And the people who have done it before and are going to do it again, what are they all going to say? Well in the history of the See’s Candy Company they always say, “I never did it before, and I’m never going to do it again.” And we cashier them. It would be evil not to, because terrible behavior spreads.

The realization that your choices protect your employees from the influence of evil behavior can immediately turn weakness into steely resolve.

The Hard Call to Fire on Performance

It’s much easier to make the call to part company when someone has violated an ethical boundary. A far more difficult challenge is to make a decision based on low (or even mediocre) performance on the job.

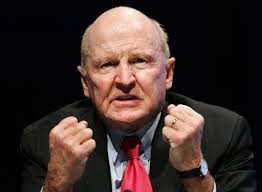

Jack Welch on ‘Rank & Yank’

One of the most famous managers of all time, Jack Welch popularized the ‘rank & yank’ system, where managers grouped all members of their team into three categories: the top 20 percent, the middle 70 percent, and bottom 10%.

The middle 70 should be given coaching, training, and thoughtful goal-setting, with an eye toward giving them an opportunity to move into the top. Keeping them motivated is the most difficult part of the manager’s task, he says. “You do not want to lose the vast majority of your middle 70 — you want to improve them,” Mr. Welch says in his 2005 book, ”Winning.”

As for the bottom 10 percent, “there is no sugarcoating this,” Mr. Welch says. “They have to go.”

While this seems like (well, is) a relatively brutal process, it has a few benefits. First, it’s no secret that this is how the company works. Everyone knows that this is how it works, and what they can expect if they lag behind.

Second, the brilliant piece of this, is that it’s a forcing mechanism for managers to remove their worst-performing team members. With this policy, it doesn’t allow for manager procrastination and softness to allow underperformers to hang around for years.

Netflix on ‘Adequate Performance’

Netflix has a very progressive culture, and it’s HR practices are cutting-edge. They’ve quickly built an incredible company, and much of that is due to how they hire, fire, and manage their culture.

“The real company values, as opposed to the nice-sounding values, are shown by who gets rewarded, promoted, or let go.”

This deck from CEO Reed Hastings, suggested by Itamar Goldminz, has some very clear words. Here are the three slides that define Netflix attitude toward when to fire and how to decide:

It’s very clear what Netflix expects from it’s employees — All-star performance. Putting in their deck for all employees to see ‘Adequate performance gets a generous severance package’ sets expectations.

Mort Mandel has a similar test, outlined in It’s All About Who — knowing what you know now about their performance, would you hire them again?

Bonobos’ CEO on Sculpting a Team

What I like about Andy Dunn‘s attitude about firing is that it presumes that it’s a required part of building an organization. There’s no sense of dread or doom to it, it’s a stated fact that it’s an important skill, one that every manager will need to hone and exercise:

This is hard to say because it sounds mean: the people you fire are more important to your culture than the people you hire. It’s a half-truth, as you have to hire people who are an outstanding, but it’s an important half-truth because the best way to protect the environment is to recognize where you have erred and course correct.

You reveal that culture as a by-product of who stays and who goes, and to effectively “experiment” your way into what your culture is by learning who fits and who doesn’t — and by learning what precisely it is they are fitting into. To do this requires courage and confrontation. You muster both of these by telling yourself it’s what you must do to make the company “safe” for your best people, who should — by the way — be the only people.

It is like a sculpture revealed by what you chip away. Unlike a block of stone, though, you can add and chip iteratively, which means you don’t necessarily have to be Michaelangelo. Most companies know they have to be superb at the adding. What is less talked about is how important it is to become excellent at the chipping.

“You have to become excellent at the chipping.” I love that line, because it doesn’t treat firing as something to just get done and over with. It’s not something to merely endure — it’s a skill that must be thought about and constantly improved. Don’t just view each one as a singular event — reflect on each one to see what can be learned.

And when you improve the skill, you’re more likely to be willing to exercise it, which will also make your better at ‘chipping’, as Dunn points out:

As an organization you want to get really good at sending people off the pitch. As Jeff Weiner observes it is rare that someone takes themselves out of the game. If you develop a reputation with yourself for treating people respectfully in transition, for being direct, for generous severance, and for being proactively helpful in their search for what’s next, you will find firing people isn’t so scary. You then will be more likely to be decisive in borderline cases; if something’s a borderline case, it’s probably not.

You may even (rightfully) come to view a firing as your own atonement for getting the hiring decision wrong. Or maybe that the hire was right three years ago, but isn’t anymore. You can’t keep someone around out of loyalty; your loyalty is to the mission, not to any particular person pursuing that mission. It doesn’t matter how vital they have been historically, it is only your judgment of how important they are going forward that counts. This is a sports team, not a family.

A company that can’t fire people well is like a forest that never has a fire. It becomes overgrown, full of weeds, and it fails. A company that fails to fire people based on culture is simply a company that is never going to have a great culture.

From Dunn’s viewpoint, we see firing as an imperative skill — one we must cultivate in order to have every tool at our disposal to improve our teams.

What ‘Jeff’ is Costing You, Personally, as a Leader

This fantastic post from Rands on First Round Review is chilling. He addresses an aspect of postponing firing under-performing employees that I haven’t read anywhere else:

If you’ve gotten to the point where your Jeff has become a real and recognizable problem, the bad news is it’s probably your fault.

“If you’re lying awake at night thinking, ‘God, Jeff is pissing me off,’ your chance at a low-cost solution probably came about three months to a year ago,” Lopp says. “You had the chance to improve things but you sat and waited until it actually started to hurt.”

“But you’re not thinking about all the other people on your team who have problems with Jeff — Angela and Frank who know Jeff is a problem but every day see you not doing anything about it. I guarantee you, whatever you believe Jeff is costing you, it’s really three to five times that. The non-obvious cost is all the credibility you’re losing as a leader.”

When you’re a manager, no one is going to make the first move for you. People on your team may have hinted around it. They may have submitted subtle or even assertive feedback. But until you sit down with Jeff and try to turn things around, you’re the problem.

“This is your team. You are the manager. You are the problem.” That’s such a stark contrast from leaving the blame on the employee and taking the perspective that it’s your duty to fire them, but it’s their fault that they need to be fired. That’s a destructive perspective, and this passage is the antidote. Take ownership of the performance of every person on your team.

Ben Horowitz’ Most Important Advice

Ben Horowitz is not afraid to fire people. His book, The Hard Thing About Hard Things, is a must-read for all managers, and it has multiple chapters full of great detail on firing and the nuances of communication. Definitely get it.

When someone like Ben, who has been through brutal rounds of firings and layoffs—can distill all of his advice down into one sentence, it’s one to take to heart:

When you’re making a critical decision, you have to understand how it’s going to be interpreted from all points of view. Not just your point of view and not just the person you’re talking to but the people who aren’t in the room, everybody else. In other words, you have to be able, when making critical decisions, to see the decision through the eyes of the company as a whole. You have to add up every employee’s view and then incorporate that into your own view. Otherwise your management decisions are going to have weird side effects and potentially dangerous consequences.

Horowitz goes deeper into this in his talk, including examples and stories from his experience building Opsware. It’s a talk that, if taken to heart, has the power to transform you as a manager and a leader.

Richard Branson Hates Firing People

As you might suspect given his public persona, Richard Branson is not a big fan of firing people. Here are a few of his thoughts on when firing is appropriate from his book, Business Stripped Bare:

My philosophy is very different. I think that you should only fire somebody as an act of last resort. If someone has broken a serious rule and damaged the brand, part company. Otherwise, stop and think.

If someone is messing things up royally, offer them a role that might be more suitable, or a job in another area of the business. You’d be amazed how quickly people change for the better, given the right circumstances, and how willing they are to learn from costly mistakes given a second chance.

Branson shares the short fuse with Buffett & Munger where it comes to mistakes that affect their companies’ reputation. His approach with other performance problems is the total opposite of some others that we’ve read about so far:

I think companies can be like families, that it’s a good approach to business, and that Virgin’s created better corporate families than most. We’ve done it by accepting the fact that we have to think beyond the bottom line. Families forgive each other. Families work around problems. Families require effort, and patience. You have to be prepared to take the rough with the smooth.

There are always more ways to think about these decisions — which only makes them harder. We can use the ideas from these leaders as guidance in our own decisions, and recognize that there are always multiple options. However you build your culture — clarity and consistency are crucial, so your team knows what can be expected.

How to Fire

When to fire is the decision — how to fire is the execution. Both are crucial to get right, and damaging if mishandled. Here are some things to think about when you’ve decided it’s time to fire someone.

No Surprises

Outside of some extreme circumstances where immediate firing is called for, as Munger, Buffett, and Branson talked about, most firing comes at the end of a protracted process of underperformance, evaluation, and communication — or at least it should.

Jack Welch’s #1 Rule of Firing

No surprises here — it’s “No Surprises.” The best workplaces are built on clear expectations and candid feedback. In those circumstances, no one should be surprised if they find themselves in that bottom 10%.

The Startup CEO Field Guide on Firing

This excerpt from ‘Startup CEO Field Guide’ also reinforces this belief, with an explicit prescription for explaining this in very clear terms:

This is pulled from a section on Google Books, found and suggested by Mike Smith. It’s got some other great info on firing there — points on how layoffs are different than terminations, and some legal considerations as well.

Intervene as Early as Possible

This is Rands’ response to the problems of the Performance Improvement Plan, listed in #2 above. Using PIPs seems to be a point of contention for companies, and for good reason. They’re formal, transparent and methodical, but they’re often deployed far too late — used as proof of underperformance rather than a genuine attempt at improvement.

Here’s Rands from First Round Review again:

First is that you should want to fix something as soon as you see it go wrong, not at the very end of a long, slow decline. And second, you can’t just throw a switch and fix everything. There isn’t just one or even a couple things you can do to make Jeff better. It’s not just one conversation. It’s a lot of little things that need to be addressed over months, every day, every hour. If you’re thinking about putting someone on a PIP, your first question should be what could you have done earlier?”

There’s a reason most people are surprised when their manager asks them to go on a performance improvement plan. Of course, people are biased toward denial. But even if they suspected something was wrong, it’s likely no one articulated it to them in a way that they understood and agreed to fix. People are also biased against confrontation.

Lopp recommends what he calls a pre-PIP — essentially an agreement made between a manager and employee to improve performance without signing anything with an unspoken “or else” at the end of it. This is even easier to implement at a startup that doesn’t have a formal PIP process.

How to Avoid Feeling Guilty

Many managers avoid firing because of the associated feelings of guilt that come along — this section will show you why you don’t have to let that feeling dominate this process.

This Podcast from Reboot, with the founders of JW Player offers great reflection on guilt and firing, everything from parting with a Co-founder to early team members.

When asked whether they felt guilt at putting the interests of optimizing for the business ahead of people, the CEO had a terrific response:

“That’s exactly the construct that produces guilt — the assumption that those are at odds. I’ve got 100+ other people working their butts off building this company. I’m optimizing for those people”

In order to protect the interests of the rest of your team, you must handle underperformers — and do not feel guilt. Here’s what the CEO had to say:

Guilt is a function of ego aggrandizement. It actually takes the pain of the situation and makes it about us, under the guise of caring about the other person. Remorse is focused on the other person’s suffering.

So do not ask yourself if you feel guilty — ask if you feel remorse. Do you feel like you’re doing the wrong thing? Or does doing the right thing just feel hard?

This conversation is full of some great points on firing, and well worth a listen. Thanks to Jonathan Howard for the recommendation!

How to Maintain Order and Confidence

Firing poorly can have some very detrimental side effects to the morale and loyalty of the rest of your employees. Communicating clearly with the whole organization is crucial for firing to be executed well.

Ben Horowitz’ advice from before applies here as well:

“you have to understand how it’s going to be interpreted from all points of view.”

If you fire someone in a humiliating and public way, employees will understand that is a possibility for them as well. If you happened to humiliate a good friend of theirs, they’ll begin to resent you as well.

In fact, that’s Jack Welch’s Rule #2: Minimize Humiliation.

Minimize Humiliation

Bill Campbell is the most famous CEO coach in Silicon Valley. He provided counsel for Eric Schmidt, Steve Jobs, and many more — and he believes the same thing. Here’s his advice as quoted by Ben Horowitz:

You can take somebody’s job, you have to take their job, but you don’t have to take their dignity. This is something Bill Campbell taught me. It’s not necessary to get up in front of the company and say, “I blew that motherfucker out. I capped his ass.”

In fact it’s not good. Nobody feels good about that. You might feel proud of yourself but nobody else feels good about that. The right thing to do is thank them for their work. Let people know that they’re moving on. You don’t have to explain all their personal details. It’s more important to leave them with their dignity and let them go on to live another day.

What you say at that meeting is their reputation, because everybody in your company is going to call on that person when they try and get their next job. If you start saying a bunch of BS about them, that’s not going to be good and it’s not going to get interpreted as we screwed up, it’s going to get interpreted as he screwed up. You have to be very honest with them but you have to make sure you preserve their dignity when you talk to the company.

No matter what the circumstances are for someone being fired, there’s no reason to humiliate them, and it benefits no one. Your team will see and appreciate that you respect them, even if a professional relationship has to end.

Communicate with the rest of the Team

Another important thing to realize is that anyone around the employee in question is also concerned for their jobs. This departure will affect their work, their team, and their output. They deserve to be informed. Also, understand that in the absence of correct information through communication from the company, there will be dubious information spread through rumor.

This is clearly something that ‘Rands’ has been through in his career, because there’s a strict policy on communication around firing at Palantir. Here’s another excerpt from Rands’ post on First Round:

At Palantir, we make a point of crushing rumors. We not only talk to the person in question, but to the people who know them well. That said, remember that people love to gossip, so you need to be very thoughtful about what is the respectful amount of information to share.

If people are talking about someone’s performance, you want to make it clear that you’re aware of the issue and investing in its resolution — that it’s being handled.

If you’re actually letting someone go, then your team’s number one concern is going to be whether everyone is getting fired. You can allay those fears while respecting confidentiality. Develop a communications plan around it. That’s an important part of the healing process.

What the rest of the team sees, hears, and feels

A good illustration of that is this short story featuring the leadership of Richard Branson at Virgin Airlines. When new planes were making the position of flight engineer irrelevant, hundreds of people had to be laid off. The alternative was becoming immediately non-competitive. So they did, but they compensated them well for the inconvenience:

It was far more than the legal minimum, and I think most of them appreciated the gesture. It was a decent package. The engineers thought it fair and — just as important — so too did their colleagues who were staying on with the company.

This is a prime example of Ben Horowitz’ point about taking in all perspectives. If current employees feel you’re treating their team poorly on their way out, they are likely to lose faith and loyalty to you — even if they keep their jobs.