Proposing a new Mental Model: Working General to Specific

How sketch artists, physicists, investors, and engineers create estimates to move quickly and avoid mistakes.

I’ve spent a decade slurping up everything I can find about Mental Models (starting with Poor Charlie’s Almanack, continuing with Farnam Street, and recently Latticework).

Now, I seek new ideas to make my thinking easier or more accurate. Discovering a new mental model is a very nerdy kind of rush for me — it’s thrilling to take a new idea and run through different disciplines. I test a new model for usefulness in many contexts… most don’t pass.

This new model does: “Working General to Specific”

It was first explained to me by a friend (Jesse) who was showing me his sketches — he’d been to art school for drawing. I asked how it was possible to achieve this kind of photorealism, and he showed me from a clean sheet of paper.

“Sketch artists are taught to work general to specific,” he said as he worked. From a blank sheet of paper, the first things they’ll draw for a landscape is a rough, straight line for the horizon. For a portrait, a rough oval for a face. They keep adding lines of general shapes, and work those until they are in correct relation to each other by shape — not detail.

“Blocking” stage of a sketch

Detail work comes only when all of the general lines are correct, and most shapes are represented. This detail work happens in a tiiiiiiiiny section, one at a time. The artist almost “zooms in” (and really, they do tend to put their face weirdly close to the paper) and do shading of a postage-stamp-sized area, one at a time. Also, Sketch artists take the opportunity to do detail work as it comes, not simply left-to-right or top-to-bottom.

Progression of a sketch from general to specific

This is the secret of Jesse’s accuracy, and also his speed. Working general to specific ensures his time is efficient. Detail work that has to change later is precious time and effort wasted. Doing the general work thoroughly first prevents waste and frustration.

The “Working General to Specific” seed was planted in my brain-grooves, and over the past two years, I’ve collected other stories in this pattern from other disciplines. When a basic idea has been independently derived from multiple disciplines (art, physics, investing, and entrepreneurship) — it is a very solid idea.

“Make the big, no-brainer decisions first.”

- Charlie Munger

The first supporting example was the concept of Fermi Calculations, a common early problem-solving step used by Physicists and Engineers. The practice is a very rough calculation to try to get the correct order-of-magnitude of the answer. This may be enough information to proceed, or help guide and double-check a more precise calculation.

This is a simple Fermi Calculation in a passage from Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality (a rationalist fanfic of Harry Potter. Yes, I’m great at parties.)

The mounds of gold coins looked to be about sixty coins high and twenty coins wide in either dimension of the base, and a mound was pyramidal, so it would be around one-third of the cube. Eight thousand Galleons per mound, roughly, and there were around five mounds of that size, so forty thousand Galleons.

For a more complicated version from a real-life scientist, instead of a fictional character based on a fictional character, here is an example from Randall Munroe (of XKCD)’s brilliant book, What If?

Question: Has Humanity Produced enough Paint to cover the whole surface of the earth?

Fermi Calculation Answer: Let's suppose that, on average, everyone in the world is responsible for the existence of two rooms, and they're both painted. My living room has about 50 square meters of paintable area, and two of those would be 100 square meters. 7.15 billion people times 100 square meters per person is a little under a trillion square meters—an area smaller than Egypt.

I’ve also seen this idea (and specific technique) used often in business settings. Successful investors I know often refer to the “Napkin Math” — the very high-level, rough estimate of a deal. “If a deal doesn’t look good on a napkin, it won’t look good in a spreadsheet.” The risk of a spreadsheet is that there are more places to hide, more assumptions to tweak. If a business looks bad on a napkin but good in a spreadsheet… it could be a dangerous deal.

“It is better to be roughly right than precisely wrong”

- John Maynard Keynes (Economist)

When working from general to-specific, you get roughly right first, so you are never precisely wrong. Problem-solving this way, you increase your “correctness” or your “completeness” iteratively while remaining oriented within the big picture.

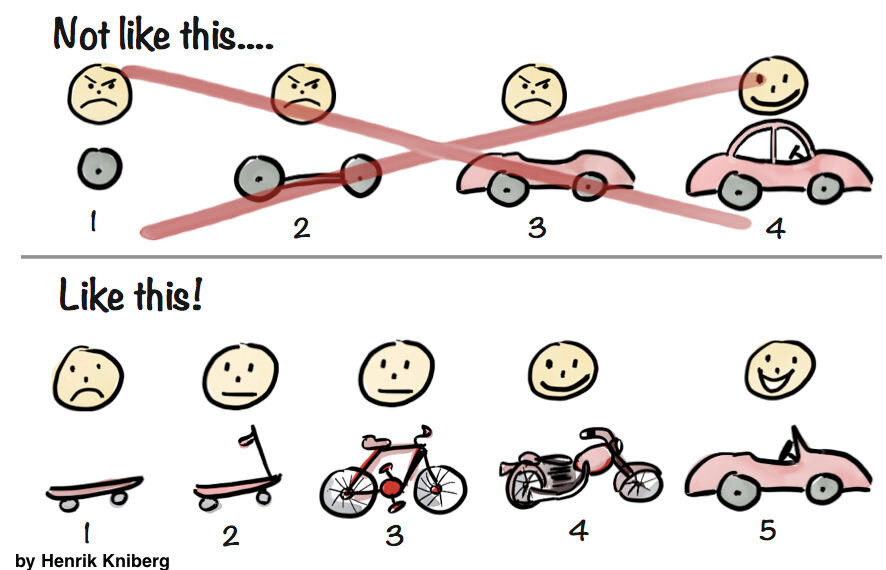

The General-to-Specific mental model is also supported by tenets in the tech world of a Minimum Viable Product or Doing Things that Don’t Scale — you want to prototype or duct tape together a complete solution as cheaply and quickly as possible, and offer it to customers.

This visual metaphor is a good way to appreciate what is a complete solution. Avoid designing a steering wheel (detail work) before you know that customers will pay for accelerated transportation (general work).

The goal of the MVP is to get roughly right — to take your idea to customers as quickly as you can in a way that gets you validation.

Once you have the customer’s problem and your solution right in a “rough sketch” kind of way, you can start to fill in the important detail work. Many startups lose valuable time and energy over-optimizing the wrong detail work, which they later find was wasted. Focusing on general-to-specific, iteratively, will keep you oriented on the right level to focus, and help you invest in the right areas of detail, at the right time.

I imagine there are many more examples from other industries and disciplines, and I welcome Architects, Jigsaw Puzzle Experts, Gamblers, and more to add more examples and stories of their own.

Links for further reading: